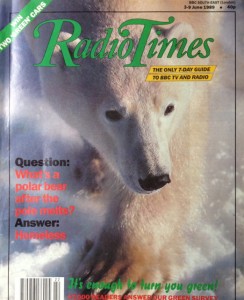

In June 1989 I wrote an article published in the Radio Times, entitled “Warming to the Problem”. It was based on an interview with the producers of a BBC2 documentary, one of the earliest (it was possibly even the first) on what was then referred to as the greenhouse effect.

In June 1989 I wrote an article published in the Radio Times, entitled “Warming to the Problem”. It was based on an interview with the producers of a BBC2 documentary, one of the earliest (it was possibly even the first) on what was then referred to as the greenhouse effect.

The introduction read:

Our planet faces an environmental crisis on a scale unprecedented in human history. In the first part of our special green issue, GHD explains the greenhouse effect. Chris Baines follows up with practical ways we can all help solve the problems, and the reports continue in an EarthWatch special starting on page 73.

This is the article.

Earlier this year, the environmental group Ark sent a glossy holiday postcard to journalists, showing Blackpool as an island, and seahorses racing on a submerged Doncaster racetrack.

They were no tourist gimmick. Ark followed the postcards up with the now-famous map of flooded Britain in the year 2050. For the first time people could see in graphic terms the dramatic changes to our familiar island shape that could take place if the sea rises by the 5 m Ark predicts.

Bryn Jones, Ark’s director, admits that the choice of date was arbitrary: “We took the hardest possible case because we have only one Earth and we must take no risks with it.” Certainly no other media event has done as much to impress on us that global warming is not about the northward spread of Mediterranean-style street cafes to Birmingham, but could mean uncomfortable and destructive changes for us all.

To mark United Nations World Environment Day on Monday, which this year takes global warming as its theme, Nature has conducted a detailed analysis of a phenomenon likely to shape our futures. The special world-ranging 90 minute programme, Climate in Crisis, presented by Michael Buerke, will assess the possible consequences for mankind and show the steps we can take to slow or even stop the warming.

Scientists cannot yet predict with any certainty what next century’s weather will be like on a warming globe. They estimate a worldwide average temperature increase of between 1.5°C and 4.5°C. Sea level rises could range from Ark’s 5 m to as low as 1 m, but even that could cause enormous damage worldwide. Half the world’s people live in coastal regions, and the poorest will be most vulnerable.

And as they speed up their research programmes, the experts agree on one thing: there is no time to wait for clear evidence that the change is taking place. We must act soon.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the most important of 40 known greenhouse gases, accounting for half the greenhouse effect. It is produced by the burning of fossil fuels, particularly in power stations. Fossil fuels are being used at an increasing rate such Third World countries as China and India. Some experts predict a doubling of CO2 in 60 years.

The burning of tropical forests is another important source, creating up to a quarter of the CO2 released into the atmosphere. 500m t of CO2 was released from Amazonian forest burning alone in 1987, a sixth of the annual global accumulation in the atmosphere. These fires are doubly damaging: burning releases CO2 and removes an efficient sink – each living tree absorbs CO2 in the air and locks it up.

Methane, the second most important greenhouse gas, is released from cattle dung, agriculture (for instance through rice growing in Asia), from drained peat bogs, and from rubbish dumps. Developing countries discharge 425m tonnes of methane annually. Indian cattle and crops are the largest single source of methane; intensive cattle grazing in South Africa and America is another big producer.

CFCs – chlorofluorocarbons – in aerosols and fridges also damage the ozone layer, and produce the most damaging greenhouse gas. The growing use of CFCs and fridges in the world could offset reduced use in the West.

Nitrous oxides are released from agricultural chemicals and fertilisers and the burning of fossil fuels. Vehicle exhausts are an important contributor. Low-level ozone is another greenhouse gas, formed in urban photochemical smogs in car dominant cultures such as Los Angeles, Mexico City and other large cities around the globe.

Everybody, in a small way, is to blame. The Syrett family’s innocent domestic routine, filmed at their Bristol home by the [BBC’s] Nature cameras, exposes us all. They use a vacuum cleaner, make toast and watch television – activities that make a tiny but cumulative demand on a coal–burning power station. They drive a car and use a lawn fertiliser and peat, sending up another whiff of greenhouse gases.

Is the greenhouse effect already with us? Britain’s mild January was followed by a snowy April, so we must be cautious. But 15 families, evacuated from the remote Carteret Islands in the Pacific by rising sea levels – as Nature exclusively reports – might consider themselves pioneer victims of the phenomenon.

The Civic leaders of Redcliffe, Queensland, commissioned a report that is so comprehensive and popular that its publication may itself consume several forests. It features the possible effects of global warming on their coastal town. It warned of wetter, stickier weather and higher seas, the flooding of their tourist beach, multiplying insect and animal pests and sewage backing up.

The meteorologists cannot yet say for certain, but the consensus is that a full-blown greenhouse effect would usher in a mean, uncomfortable world. The biggest changes could come in the tropics and sub-tropics, with the drier areas becoming drier, and humid areas becoming wetter, with more frequent storms.

What about us? In northern latitudes, winters could become shorter, wetter and warmer. Summers will be hotter and drier. Efficient EU farmers might adapt to changing conditions, and with the aid of genetic engineering actually grow more; they could be more rice grown in the vast Siberian and Canadian plains. But climatic disasters could trigger global food shortages.

They must be massive programmes of tree planting, and a rapid halt to forest burning. British scientists Dr Norman Myers estimates that trees planted at a cost of $120 m on 1.2 mi.², an area equivalent to the EC countries and Scandinavia, and already available around the globe in deforested land, would soak up 3 bn t of CO2 annually. Compare that with the estimated $100 bn it would cost to protect the vast east coast of the USA for every 1 m rise in sea level.

The crash program in energy conservation would bring big benefits through the reduced use of for fossil fuels. If all Americans used new fuel-efficient fridges, savings will allow 18 coal-fired power stations to be closed down. There should be greater use of sun, wind and wave power, which doesn’t produce greenhouse gases. The most important point is that we do something now.